- Undergraduate

- Onstage

- Opportunities

- Foreign Study

- News & Events

- People

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

The following was printed by The New York Times

June 5, 2020

written by Lauren Katzenberg, editor of the At War channel

bonus_camp_burning_withing_sight_of_washington_monument.jpg

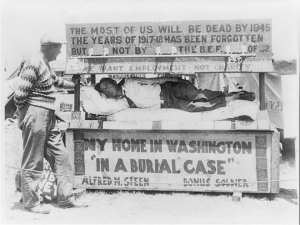

bonus_marcher_sleeping_1932.jpg

It started with roughly 250 veterans from Portland, Ore., who decided in May 1932 to travel to Washington after the government repeatedly failed to pay out a bonus that had been promised to those who had served overseas military during World War I. The country was in the midst of the Great Depression, and millions of Americans were unemployed. With little else keeping them at home, more and more men, women and children followed, making their way to the capital, where they set up sheds and tents in camps — with a headquarters situated along the Anacostia River. The mass of protesters, which swelled to at least 20,000, called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force. As noted in "The Bonus Army: An American Epic,"

a 2004 book by Paul Dickson and Thomas B. Allen, it was the largest

and most sustained demonstration of the Great Depression.

Despite widespread public support for the protesters, the Senate in mid-June voted against legislation that would pay the bonus. Instead of giving up, the veterans refused to leave Washington. And more continued to pour in to join the cause. Dispatches of daily life from the camps were published in local and national papers. They demonstrated peacefully in front of the White House and in the streets, while local officials and the police repeatedly tried to remove them from government-owned buildings and push them out of the city.

images.jpeg

Everything came to a head on July 28, after an eviction operation by the police devolved into violent clashes with the veterans. President Herbert Hoover had become impatient with law enforcement's response; he called in the Army, which had already been conducting riot training and moving tanks to the outskirts of Washington. In an assault drawn up by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, then the Army chief of staff, cavalrymen, infantry, machine gunners and tank crews tore through the streets, advancing on the protesters with bayonets and tear gas. "Men and women were ridden down indiscriminately," J. F. Essary wrote in The Baltimore Sun. "The mad dash of these armed horsemen against twenty to thirty thousand people who were guilty of nothing more atrocious than standing on private property observing the scene was bitterly commented on by spectators." Leading Third Cavalry was Maj. George S. Patton Jr.

By nightfall, the troops reached the Anacostia camp's headquarters, which they burned down, leaving little but smoldering ash. Hoover had called for a more restrained Army response, but MacArthur

deliberately ignored orders. "Flames rose high over the desolate

Anacostia flats at midnight tonight," The New York Times reported

the next day. "A pitiful stream of refugee veterans of the World War

walked out of their home of the past two months, going they knew

not where."

Their base destroyed, many protesters left Washington

and made their way back home. The movement was not completely

destroyed, however. Many returned to Washington to continue their

demands in 1933 and 1934.

Hoover attributed the Army's brutal response to a national-security threat. He said the people who remained in the camp after the Senate vote were not veterans but "Communists and persons with criminal records," The Times reported — though Communists had been explicitly barred from joining the movement in its early days and were quickly ousted by the protesters if discovered in their ranks.

While the 1932 demonstration didn't achieve what it set out to, it left a permanent stain on Hoover's presidency. The manner in which he used the Army to expel the veterans from Washington sparked outrage across the country before the fall presidential election; he lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt in a landslide. [Bonuses were finally paid out by FDR's administration in 1936.]

One thing that made the Bonus Army so remarkable was that it was racially integrated at a time when Jim Crow laws were in full force. That is perhaps why, Dickson and Allen surmise, many have dismissed its significance. In the camps, black and white people lived, cooked and ate together. There was no segregation, no Jim Crow.

Roy Wilkins,a reporter for an N.A.A.C.P. publication called Crisis,

visited the camps in June and was taken by how everyone lived peacefully

side by side. He saw it as a model for integration across the United States.

"There I found black toes and white toes sticking out side by side from a ramshackle town of pup tents, packing crates and tar-paper shacks," Wilkins wrote. "Black men and white men, veterans of the segregated Army that had fought in World War I, lined up equally, perspired in sick bays side by side. For years the U.S. Army had argued that General Jim Crow was its proper commander, but the Bonus marchers gave lie to the notion that black and white soldiers — ex-soldiers in their case — couldn't live together."

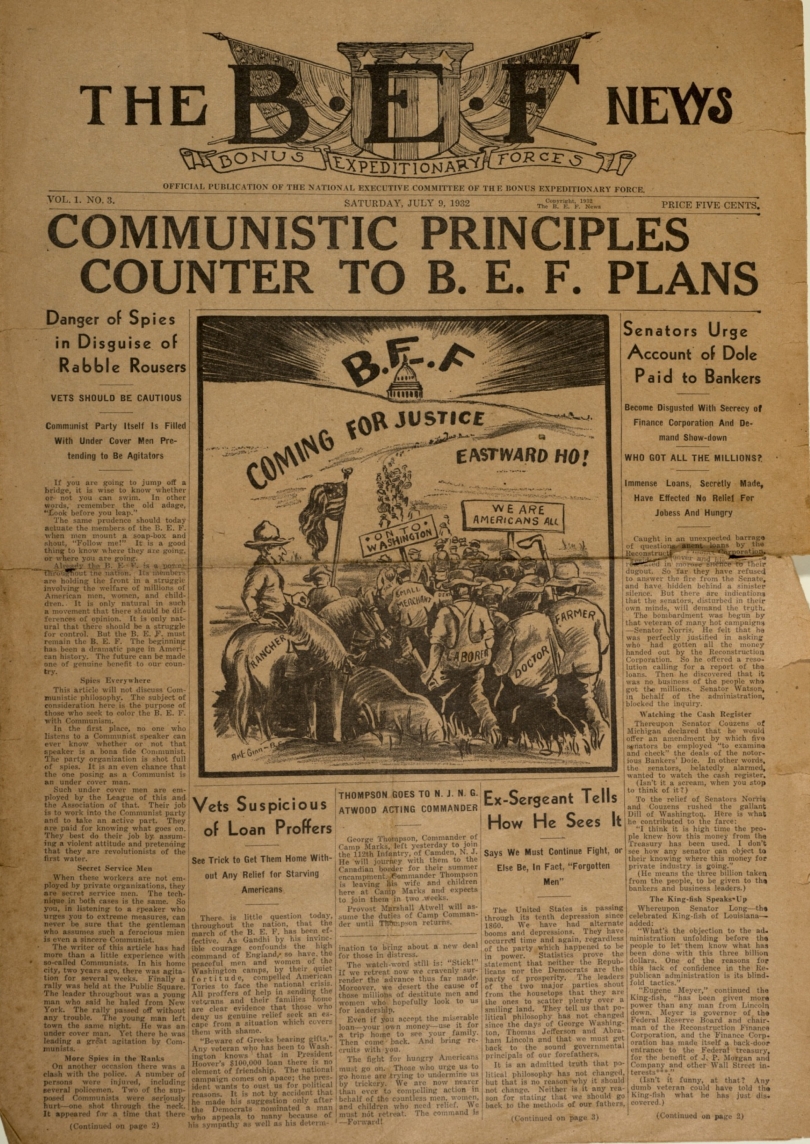

While encamped in Washington, the Bonus Army protesters developed their own community, complete with streets, stores, and a newspaper.

Events were vividly capured by the still-new medium of film and viewed by Americans around the country.

From the USC Digital Archives: Raw footage of Bonus Army encampment evictions, July 1932.

From Task & Purpose: footage of Marine Major General Smedley Butler's impassioned speech at the Bonus Army encampment, July 1932.

The Bonus Army protests and events inspired many responses from the country's creative artists.

From the Delta Blues Museum: A 2006 podcast on early Bonus-inspired Blues recordings from "Cripple" Clarence Lofton, Red Nelson, Joe Pullum, and others. Many of the earliest available Blues recordings were inspired by the Bonus March events.

From the Kennedy Center: the origins of the iconic 1932 hit song Brother Can You Spare a Dime?, recorded by Rudy Vallee, Bing Crosby, Al Jolson, and others.